States Rights Southern Rebel at heart.

Be the first person to like this.

Knew it..

random_nihilus.backup on Instagram: "I have been shadowbanned. If you appreciate the content you can help me by following and sharing before this video gets flagged.🫡

Comedy was never meant to be politically correct.

💢💢 Enter the comments

75K likes, 1,402 comments - random_nihilus.backup on March 3, 2025: "I have been shadowbanned. If you appreciate the content you can help me by following and sharing before this video gets flagged.🫡

Will be free sooner or later..

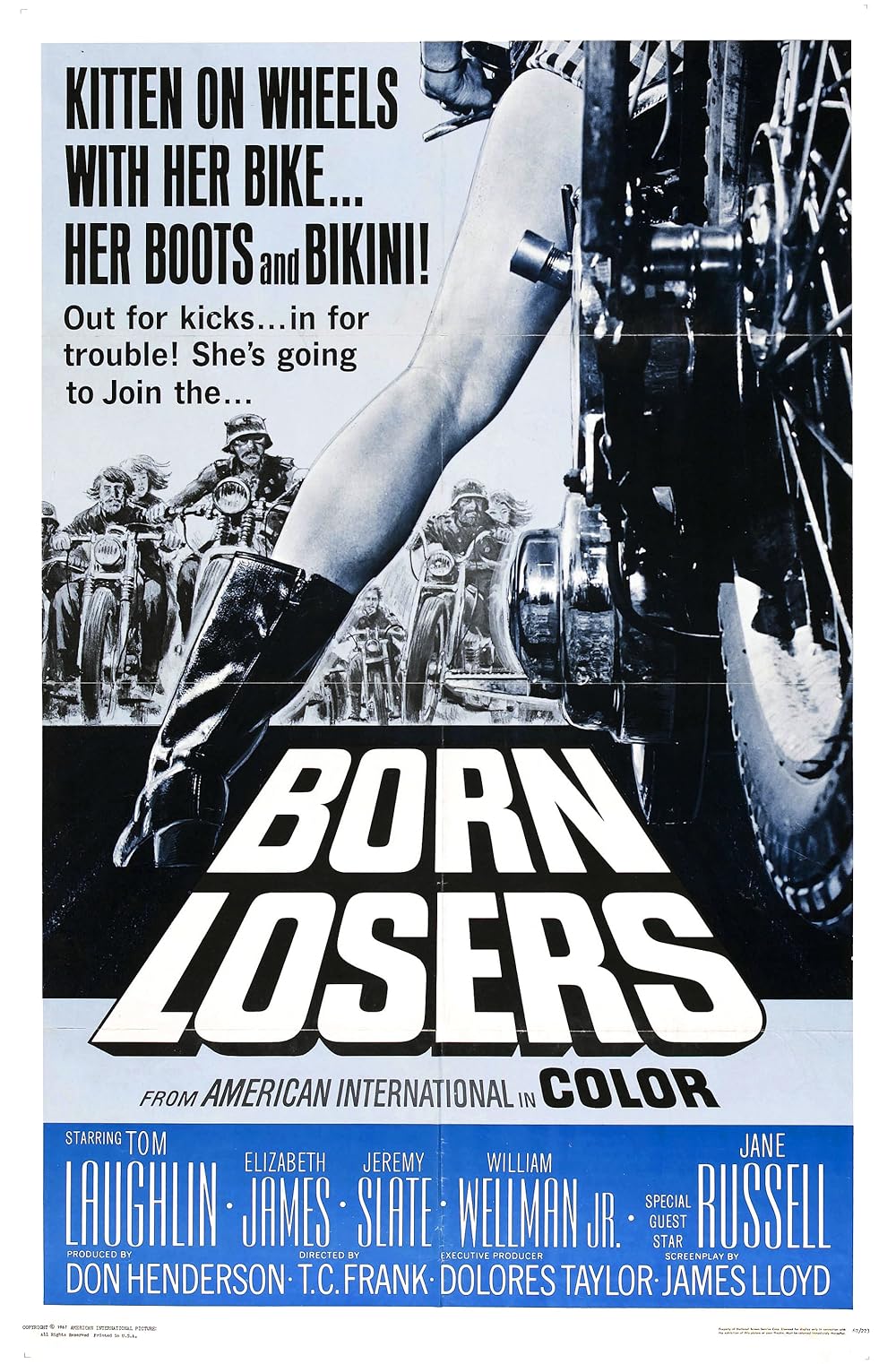

Billy Jack

Half-breed ex-Green Beret Billy Jack is driven to action when a desert school is victimized by thugs. Using his fists and his feet, he unleashes justice in a fast-kicking frenzy that made him an insta

The original Billy Jack movie, Born Losers, from 1967 is free on Tubi

https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0061420/

Full Movie

The Trial of Billy Jack | English Full Movie | Action Drama Music

Never miss a single new movie film - subscribe here - ► https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCTjxrujNCF9JSQzXE3th21A?sub_confirmation=1

The film follows a man caught in a web of conflict and legal strugg

Create our own Community Banks. Zero interest. Pays the people dividends. No more private Central Banks charging us interest and no more debt.

@reformedantihero on Instagram: "Steve!! Don't!! All we need to find is the Red Woman or Bran. This is not the way, my dude...🤫🤫🤫"

27K likes, 381 comments - reformedantihero on May 29, 2025: "Steve!! Don't!! All we need to find is the Red Woman or Bran. This is not the way, my dude...🤫🤫🤫".

Be the first person to like this.